At first sight of Vic Oliver’s Studebaker you’re mesmerized. Its two-tone paint job calms your eyes, making it a pleasure to study every angle of the exquisitely proportioned car.

Its chrome accents and white leather interior give it the chic and sophistication of a 1950s Lincoln, while its convertible two-seat design with dual fins protruding from the rear gives it the allure of a 1955 Ford Thunderbird.

The Studebaker’s characteristics add up to a familiar formula, yet when further examining the car it begins to look atypical; especially when your eyes find the gold “Speedster II” emblems at the rear of the car.

The Studebaker’s characteristics add up to a familiar formula, yet when further examining the car it begins to look atypical; especially when your eyes find the gold “Speedster II” emblems at the rear of the car.

And that’s because the car doesn’t exist – technically.

The car was originally a 1953 Studebaker Starlight. But after only eight months of extraneous work, an assortment of original Studebaker parts and a clear vision, Oliver turned the Starlight into a concept car the engineers at Studebaker never got to make.

The idea for the convertible Speedster II came from a conceptual drawing by legendary car designer Bob Bourke. The drawing was of a conceptual sports car design fashioned from production steel panels. It was meant to have the sporty, racy appearance similar to the styling feature used on Continental Mark Vs and Ford Thunderbirds of the time, according to the book Bob Bourke designs for Studebaker by John Bridges, where the original design can be found. One of the only main differences between that design and Oliver’s finished design is he made his convertible – something you would not find on Studebakers between 1953 and 1959.

The idea for the convertible Speedster II came from a conceptual drawing by legendary car designer Bob Bourke. The drawing was of a conceptual sports car design fashioned from production steel panels. It was meant to have the sporty, racy appearance similar to the styling feature used on Continental Mark Vs and Ford Thunderbirds of the time, according to the book Bob Bourke designs for Studebaker by John Bridges, where the original design can be found. One of the only main differences between that design and Oliver’s finished design is he made his convertible – something you would not find on Studebakers between 1953 and 1959.

And before Oliver had the inspiration to take on the project, the idea to make the concept a reality was originated from the previous owner of the 1953 Starlight, Jack Morris.

A few years ago Oliver went to a swap meet in Philadelphia, looking to research Studebakers and potentially find a new project. His wife, Connie, found Morris sitting with a bunch of Studebaker parts and items. They struck up a conversation and Jack told them about this Studebaker project he had with a 1953 Starlight. It was a project Oliver knew he wanted to take on.

A few years ago Oliver went to a swap meet in Philadelphia, looking to research Studebakers and potentially find a new project. His wife, Connie, found Morris sitting with a bunch of Studebaker parts and items. They struck up a conversation and Jack told them about this Studebaker project he had with a 1953 Starlight. It was a project Oliver knew he wanted to take on.

And when he came across the concept drawing by Bourke, Oliver said he thought, “I could see myself doing that.”

His passion to work on cars began in high school when he would hang out at an automotive shop in Mattydale, learning how to sculpt body work, among other skills. It was about this time when he fell in love with Studebakers, too, saying he just thought they were cool.

He had many hot rods when he was in high school and always dreamed of having his own place to work on them. But soon after life took over. He got married and had a family. His passion for working on cars had to be pushed to the side for a while.

He had many hot rods when he was in high school and always dreamed of having his own place to work on them. But soon after life took over. He got married and had a family. His passion for working on cars had to be pushed to the side for a while.

Oliver, now 65 years old, decided to retire at age 57 in order to pursue his dream. He said there are a lot of people who dream of doing something, but by the time they retire they’re too old to do so. He wanted to get out before he got too old.

From there on he spent his time working on and building a variety of classic cars before finding his latest passion project, the Studebaker. Every step of the build, from the body work to the welding to the paint, was done by Oliver.

In the eight months it took him to build the Speedster II last year, he had about 3,000 hours of work into it. Every day he worked on it were 12 to 15 hours days. The project was the biggest one he had ever attempted.

In the eight months it took him to build the Speedster II last year, he had about 3,000 hours of work into it. Every day he worked on it were 12 to 15 hours days. The project was the biggest one he had ever attempted.

“I can’t believe I did it,” Oliver said.

He sought help where he could, too. Friends and family helped along the way, and even a FedEx driver at one point. Oliver said one day when he was working on putting the rear bumper on the car, a FedEx driver was delivering a package, and he pulled him into the garage to help him out.

Oliver said, one of his biggest supporters was his wife, who like him, has a passion for classic cars. “I couldn’t have done it without her,” he said.

When building the car, Oliver said he tried to put himself in the mindset of the Studebaker engineers. He wanted to build the car the way they would have done it. That meant using all Studebaker parts and having to get creative in how he used them. Acting as the Studebaker edition of Dr. Victor Frankenstein, Oliver used an assortment of parts from 1950s and 60s Studebakers to bring his creation alive.

When building the car, Oliver said he tried to put himself in the mindset of the Studebaker engineers. He wanted to build the car the way they would have done it. That meant using all Studebaker parts and having to get creative in how he used them. Acting as the Studebaker edition of Dr. Victor Frankenstein, Oliver used an assortment of parts from 1950s and 60s Studebakers to bring his creation alive.

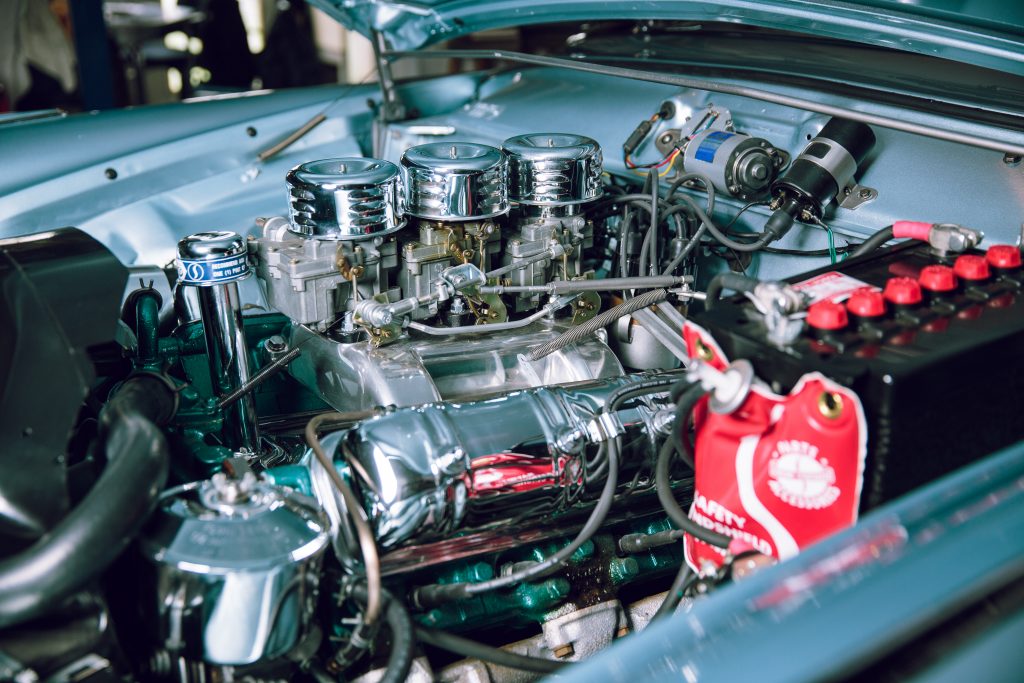

The rear fins are from a 1956 Studebaker, the dashboard from a 1960s Studebaker, the fender trims from a 1950s Studebaker, and so on. The two-tone blue paint is of his own choosing, though. He just liked the color scheme, he said. The only custom part on the car is the gold “Speedster II” emblems, which Oliver had a local jeweler make. Under the hood is a 289 V8 engine, which is attached to a 4-speed manual transmission.

The rear fins are from a 1956 Studebaker, the dashboard from a 1960s Studebaker, the fender trims from a 1950s Studebaker, and so on. The two-tone blue paint is of his own choosing, though. He just liked the color scheme, he said. The only custom part on the car is the gold “Speedster II” emblems, which Oliver had a local jeweler make. Under the hood is a 289 V8 engine, which is attached to a 4-speed manual transmission.

Oliver calls it a 1955 Speedster II.

“I love every part of the car,” Oliver said. “I can’t get tired of staring at it. No one has seen anything like this, even Studebaker people.”

But soon many will. As part of a special exhibit, Oliver’s Studebaker will be placed in the National Studebaker Museum in South Bend, IN for about six months. For those as passionate about Studebakers as Oliver, the car is sure to catch their eye and draw it to every perfectly proportioned section of the car. They’ll be mesmerized at first sight.

But soon many will. As part of a special exhibit, Oliver’s Studebaker will be placed in the National Studebaker Museum in South Bend, IN for about six months. For those as passionate about Studebakers as Oliver, the car is sure to catch their eye and draw it to every perfectly proportioned section of the car. They’ll be mesmerized at first sight.

Words by Nick Graziano and photos by Chris Penree

I have to believe that he started with a Starliner, not a “Starlight” model.

There is a published shot of an actual full size clay of a T-bird length roadster with a toned down version of the 1955 grille done by Bob Bourke’s team for the Studebaker lineup, and

devoid of the profile clutter seen here. Gene Garfinkle did a side elevation sketch of it at

the time of a Road & Track article introducing the Avanti entitled “After Ten Years.” Sorry I cannot locate and scan those for this comment.

It is too bad Studebaker couldn’t make the rear fenders one piece without the stainless steel strip on top to cover the joint. If a one piece fender could have incorporated the tail light housing and the front fender incorporated the headlight housing it would have been the cleanest and most beautiful design ever. I had one in the early 60’s. It could have used the dash and bucket seats from the Golden Hawk, a stiffer frame and a Chevy 350.